The Burrow

Climate policies of governments worldwide are under constant scrutiny as the world inches closer to irreversible climate change. As a result, there are many different ways governments can go about trying to reduce their involvement in fossil fuels.

One such way is divestment, which in its simplest terms, is the selling of stocks and/or bonds in previously invested assets – the exact opposite of investment. As experts in energy comparison, we thought we’d take a look at the changing landscape of the fossil fuel industry through divestment.

Before we dive deep into the schematics of fossil fuel divestment, we wanted to see the lay of the land and look to understand what people generally already know and perceive about divestment. We did this by surveying 2,518 adults across Australia and North America.

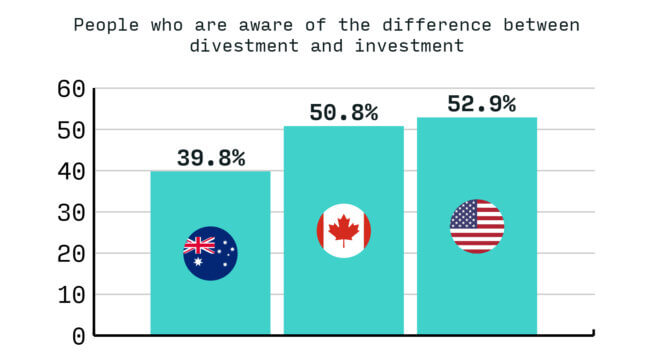

While there is general underlying knowledge of divestment, Australians lag behind Canadians and Americans in understanding the difference between investing and divesting.

In Australia, just under 40% of people surveyed said they understood the difference between investing and divesting, whereas more than 50% of Americans and Canadians said the same.

We also found that there was a surprising divide between the number of men who knew the answer (an average of 58.13% across the three countries) and women (37.10%).

We were also curious about people’s sentiment toward fossil fuel investment options from different companies. Our survey found that Americans were the least likely to care about a companies’ investments, with 27.8% of people stating as much. On the contrary, 43.3% of Australians had said that they don’t agree with companies’ decisions to invest in fossil fuels and think they should invest in greener alternatives, whereas just over a third of Canadians don’t agree with fossil fuel investment; instead, they believe that what organisations choose to invest in is not their choice.

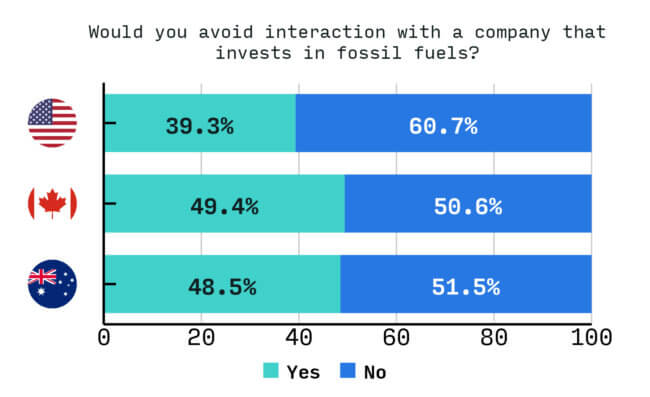

Lastly, we wanted to see if thoughts and perceptions would impact people’s behaviours against companies that invest in fossil fuels.

Australians and Canadians find themselves on equal footing, with almost one in two people willing to avoid interaction with companies that invest in fossil fuels, whereas only 39.3% of Americans would do the same.

Read on below to learn more about what fossil fuel divestment means and what countries and companies can do to minimise their energy impact.

Celebrities Leonardo DiCaprio and Natalie Portman are advocates, Desmond Tutu compares it to the divestment and sanctions against South Africa during apartheid, and the world’s biggest investor, Blackrock, has even promised to get on board.

It’s a decade since the birth of the fossil fuels “divestment” movement.

The opposite of “investment”, divestment means selling assets. Here it means getting rid of investments in fossil fuel companies, with the aim of curbing climate change.

The movement kicked off in earnest in late-2011, when students at Pennsylvania’s Swarthmore College, on the US East Coast, called on their university’s endowment to “immediately divest” from coal.1 It quickly mushroomed.

By the end of 2012, campaigns calling for administrations to exit their coal, gas and oil investments had sprouted on the campuses of dozens of colleges across the US.2 Among them were those of the prestigious Harvard University, Stanford University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The high profile of those colleges – and that they collectively manage tens of billions in “endowments” – drew international attention to the student campaigns.

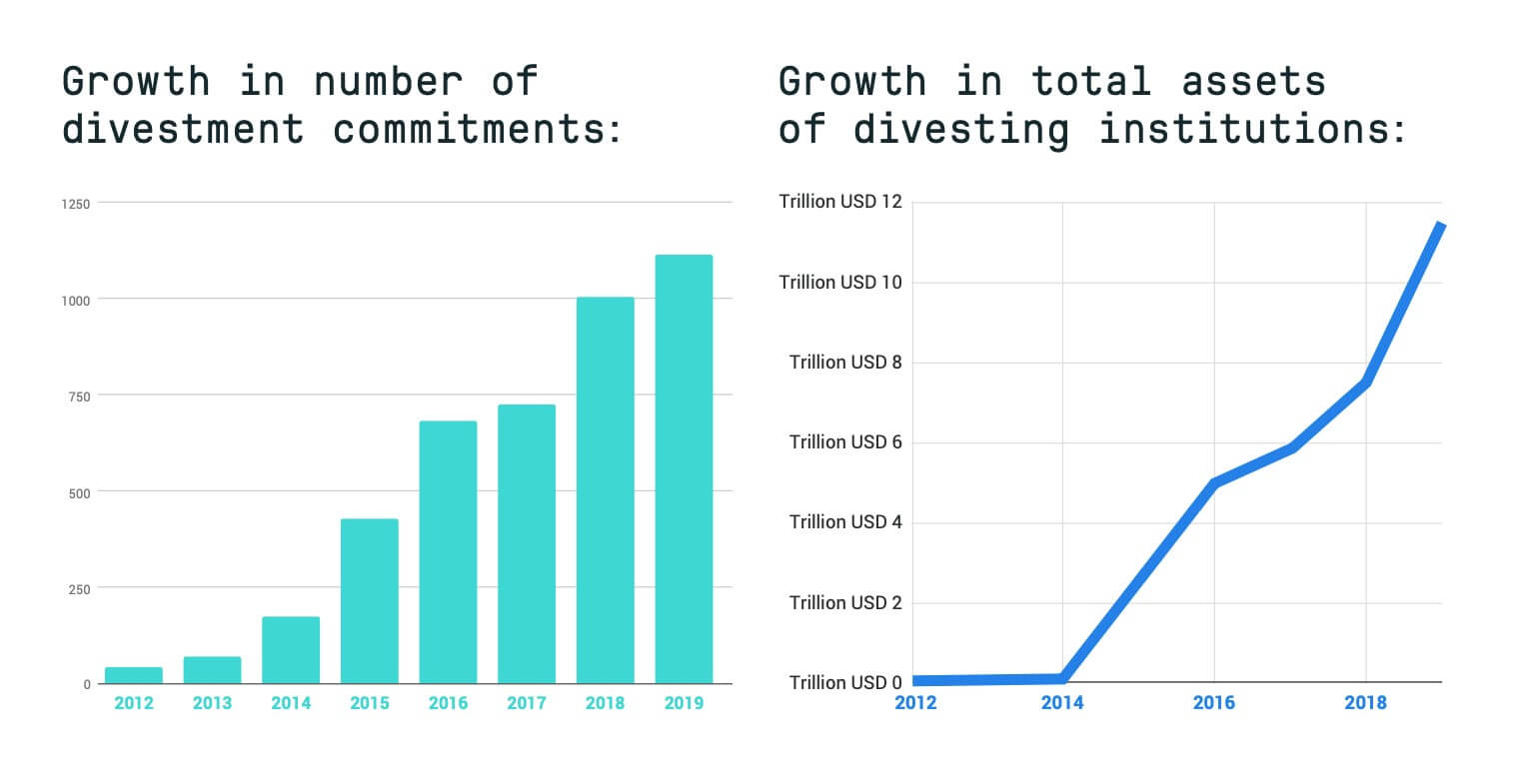

By 2013, Oxford University research found it was the fastest growing divestment movement in history, faster than campaigns that targeted apartheid, tobacco and armaments.3 By 2015, according to US not-for-profit DivestInvest, which has been tracking the sector from the start, 436 institutions representing US$2.6 trillion(tr) had pledged fossil fuel divestment.4

There are currently, according to DivestInvest, over 1,300 institutions across 49 countries – collectively holding a massive US$14.1 trillion in assets – that have pledged fossil fuel divestment in some form.5

“Ditching fossil fuels from one’s portfolio has moved swiftly from a ‘radical’ stance taken by a handful of smaller institutions purely on moral grounds, to a mainstream consideration for some of the world’s largest investors,” the group says.

But has any of it made any actual difference? In a word: Yes. But it’s a little complicated.

Global fossil fuel divestment commitments. Source: DivestInvest5

Global fossil fuel divestment commitments. Source: DivestInvest5

In January 2021, the highly regarded Journal of Economic Geography published a ground-breaking study conducted by a team of five researchers from a string of the world’s top universities, including the UK’s Oxford University and University College Dublin.6

It’s the first study into whether the fossil fuel divestment movement has been successful in its goal to decrease the amount of new capital raised by fossil fuel companies.

The issue is important because whether average temperatures are kept from rising by more than 1.5C or 2C – and so whether humans are spared from the worst effects of global warming – hinges on how much oil, gas and coal is extracted and burned in the coming years.7

The researchers analysed 19,057 fundraising transactions involving oil and gas (though not coal) companies based in 33 countries between 2000 and 2015. It used data from so far back as 2000, to account for fundraising by fossil fuels both before and after the divestment movement began.

They compared the oil and gas fundraising against the level of fossil fuel divestment commitments made by institutions in each of the 33 countries.

The study makes allowances for a wide range of factors, including a country’s wealth, its remaining fossil fuel deposits, its level of renewable energy generation, and how pro-environmental or pro-fossil fuel it is (measured by the stringency of its environmental laws on one hand, and on the other, the level of subsidies it provides to fossil fuel companies).

Led by Dr Theodor Cojoianu of Queens University Belfast, the researchers found the more divestment pledges in a country, the less capital flowed to its oil and gas companies.

“In the years in which countries witness a stronger fossil fuel divestment movement…the oil and gas sectors fundraise less compared to its historical average,” the study found.

And how effective the movement was in a country was dependent on that country’s broader environmental stance. Pledges were “enhanced” in countries with “more stringent environmental policies” – for example much of Scandinavia and Europe – but “diminished” in countries which “heavily subsidise fossil fuels”, the researchers found.

The UK – where environmental policies are relatively stringent – has been one of the movement’s biggest success stories, Cojoianu’s team finds in a related study.8

There, oil and gas companies raised an average of $16.5bn every year between 2000 and 2015. Yet for every $1bn increase in divestment pledges from UK institutions, the researchers found there was a substantial $350m decrease in fundraising by the UK’s oil and gas companies.

How effective divestment pledges are also depends on who’s making them.

The study published by Journal of Economic Geography breaks down pledging institutions into two categories:

It further broke down the non-financial institutions into:

The researchers found that for every 1% increase in the total value of fossil fuel divestment pledges made in a country, the total amount of money raised by oil and gas companies in that country fell by 0.13%.9

But Cojoianu’s team found that pledges from “non-financial” institutions, such as universities, non-government organisations and religious groups, had an outsized impact. For every 1% increase in divestment pledges made by non-financial organisations, the amount of money raised by oil and gas companies fell by 0.2%.

Drilling down further showed it was non-government organisations that had the greatest impact: a 1% increase in pledges translated to a 0.25% drop in oil and gas fundraising.

In overall terms, the amount of money invested in fossil fuels by education and religious groups is relatively minor, yet those pledges have had an outsized impact. Much of this is due to the high-profile nature of many of those institutions.

For example, one of the highest-profile movements has been Divest Harvard. And that’s despite its campaign to have Harvard University divest its endowment, currently worth US$41bn, having been unsuccessful.10

A February 2015 “sit-in” by students pushing for divestment failed to sway the university. But the following week the students’ plight made global headlines when a group of “notable” Harvard alumni – including actor Natalie Portman, film director Darren Aronosky and author Susan Faludi – wrote to Harvard’s administration supporting the students and denouncing the university’s failure to divest from fossil fuels.11 In September that year actor Leonardo DiCaprio also lent celebrity power to the movement, pledging to divest his own investments, along with those of his multi-million dollar environmental foundation, from fossil fuels.12

Another factor for their outsized impact could be that education facilities and religious institutions were among the movement’s first major adherents. Currently, faith-based groups represent 34% of the 1326 institutions that have made divestment pledges, about half of them Catholic.13 Researchers say the “moral” or ethical component of divestment has been a strong driving force.14

In 2014, Nobel peace prize winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who was a key figure in the global sanctions movement against South Africa during apartheid, called for a similar movement against fossil fuel companies.15

“People of conscience need to break their ties with corporations financing the injustice of climate change,” Tutu wrote.

“It is clear [the companies] are not simply going to give up; they stand to make too much money.”

The findings of Cojoianu and his team appear to back up Tutu’s sentiment. They found that pledges from financial institutions were effectively meaningless.

More scientifically, the researchers found that for every 1% increase in divestment pledges made by financial institutions in a country, there was no significant change in the amount of money raised by that country’s oil and gas companies.16

The finding is particularly important because financial institutions are the key funders of fossil fuel projects, and their actions will heavily impact on whether global warming can be kept within the 1.5°C – 2°C target.17

Financial institutions have also become some of the biggest participants in the divestment movement, bursting on to the scene ahead of the December 2015 Paris UN climate talks. In September 2014, 181 institutions controlling US$50bn in assets had made fossil fuel divestment pledges.18 By September 2015 there were pledges from 436 institutions controlling US$2.6tn – a monster 50-fold increase.19

It was financial institutions leading the charge. “In 2014, foundations, universities, faith-based organisations, NGOs and other mission-driven organisations led the movement,” according to US researcher Arabella Advisors.20 By September 2015, “large pension funds and private-sector actors such as insurance companies” – represented “over 95%” of total assets earmarked for divestment.

Yet the authenticity of such claims from financial institutions, along with other stated “green” credentials, have long been drawn into question.

For example, the world’s biggest investor, Blackrock, which manages US$8.7tn globally, made international headlines in January 2020 when it announced a pull-back from coal.21

Its CEO Larry Fink said climate change meant the world was on the “edge of a fundamental reshaping of finance”, however the company’s intentions were met with some scepticism, especially from some environmental groups.

One year on, in January this year, it emerged that Blackrock still held US$85bn worth of investments in coal companies, and it was alleged the group was using “loopholes” to overstate its commitment to fossil fuels divestment.22

For example, Blackrock’s divestment pledge still allowed it to invest in companies earning less than one-quarter of their revenue from coal, and they only pertained to its “direct investments”, not the US$5tn-plus it held in “index” funds, which passively track the broader stock markets.

Despite this, Blackrock’s green position appears to be slowly improving. It has long been criticised for hypocrisy by claiming to be green while simultaneously voting against shareholder movements calling for action to address climate change. In September 2020 the group disclosed that in the preceding year it had voted 55 times against directors at 49 companies for failing to take sufficient action to address climate change.23

For many individual countries, particularly those in much of Europe and Scandinavia, the fossil fuel divestment movement has been undeniably successful.

And the Statistical Review of World Energy, a highly regarded series which has been published annually by energy giant BP for the past 70 years, shows there has been strong growth in renewable energy generation in countries with strong divestment movements.24

For example, in France and Germany, renewable energy generation grew at an average rate of 16.5% and 11% a year respectively over the decade to 2018. Last year renewables, including wind and solar, accounted for 8% of Germany’s total energy.

In the UK, renewables have grown at an average annual rate of about 20% over the past decade.

Yet despite the divestment movement’s successes, there remains an elephant in the room: oil and gas investments have continued to surge over the past decade.

“While we find that the divestment movement has an effect on capital flows within individual countries, at an aggregate level across our 33 countries, oil and gas financing has nevertheless continued to increase at an average rate of c. 8% per year since the movement started,” the researchers write.9

One explanation for this, they say, is the “unintended consequence” of financial institutions shifting to foreign markets. The study found that in countries where environmental controls are stringent and there are high levels of divestment pledges, domestic investment banks are more likely to finance oil and gas projects offshore.

“For social activists seeking to impact fossil fuel investment, our paper shows that it is not enough to monitor the finance that investment banks provide to domestic fossil fuel companies,” the authors write.

“They also need to pay close attention to foreign investments that the targeted investors make, and to the broader context of their home government’s environmental policies.”

When releasing the Statistical Review of World Energy in 2020, BP CEO Bernard Looney said the technologies required to reach net zero carbon emissions “exist today” and that he was optimistic this would happen.25

“The challenge is to use them at pace and scale, and I remain optimistic that we can make this happen,” he said.

There are two major limitations of the Cojoianu study, which are intimately linked. First, it excludes coal, the dirtiest of fossil fuels, which currently accounts for around 30% of the globe’s CO2 emissions and presents the single biggest threat to the climate.26

Secondly, the fossil fuels divestment movement is overwhelmingly an Anglo-American one.

On its website, DivestInvest claims that more than 1,300 institutions have committed to pledging, from 49 different countries.27 Yet the pledges are overwhelmingly from Western Europe, Scandinavia, North America, and to a lesser extent, smaller countries such as New Zealand.

Compare the Market has crunched the numbers.

The six nations with the most pledges, by number of institutions, are the US (374), UK (252), Australia (194), France (59), Canada (46) and Italy (31). Together they represent almost 80% of all pledges.In dollar terms, the biggest pledges (that is, by the amount of assets controlled by the entities doing the pledging) from 2008-18 were:

Norway tops the above list thanks to a single pledge – a divestment commitment from its monster sovereign wealth fund (US$1tn-plus).28

In France and Germany, most of the pledges come from local and regional governments, with the governing bodies of Paris, Lyon, Berlin, Stuttgart and Leipzig among those pledging fossil fuel divestment.

But one of the biggest takeaways from the DivestInvest data is that in the oil rich states of the Middle East, and in major emerging economies such as China, the fossil fuels divestment movement is almost non-existent.

The global position of the fossil fuel divestment movement takes on a different complexion when moving outside the industrialised western nations.

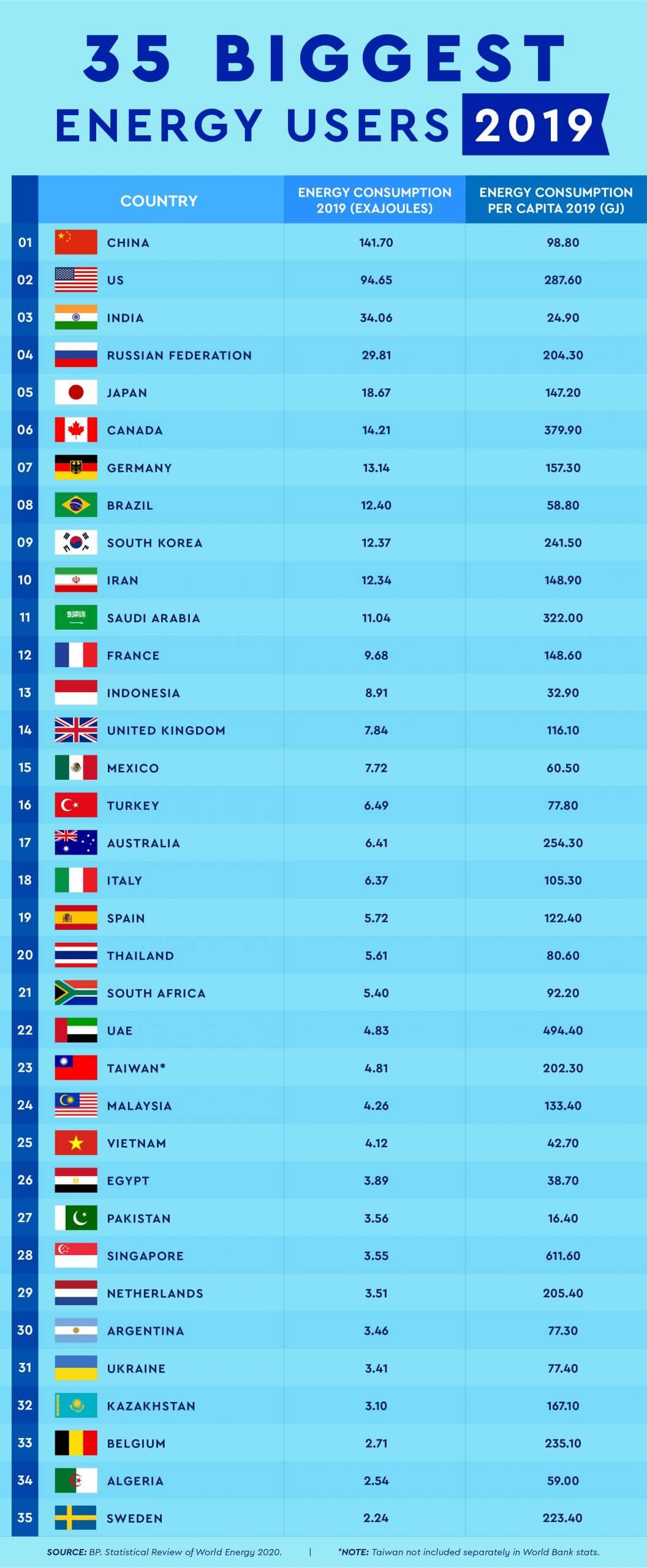

Coal is the biggest threat to the climate and China is overwhelmingly the biggest user of coal. China is the biggest source of CO2 emissions, responsible for about 28% of emissions globally,29 and while most of the world is moving away from coal, China is ramping it up – in a big way.

“While appetite for new coal power development slowed through most of the world in 2020, it ramped up in China,” said a report released in April by US group Global Energy Monitor.30

“The country was home to 85% (73.5 gigawatts) of the 87.4 GW of proposed new coal fired capacity throughout the globe in 2020, leading to the first annual increase in the amount of global coal power under development since 2015.”

While many countries are yet to agree to emissions targets, China’s president Xi Jinping has said the nation will aim for “carbon neutrality” by 2060.31

However, in the face of the eye-watering projected growth in China’s coal fired-power generation, many economists and policy setters see net-zero by 2060, even if it is achieved, as too little, too late. In line with its pipeline of new coal power plants, China has by far the highest number of coal mines under construction, with over 100 underway, according to analyst Global Energy Monitor.

In its defence, China, along with other emerging economies such as India, has been late to the game when it comes to industrialisation. Developing nations argue the west has grown rich on the back of comparatively cheap coal and that, at the very least, rich western nations should compensate them and help them move to cleaner alternatives.31

The US and the UK are among those nations to have shifted away from coal power in recent years, yet the drivers in each country have been different.

Soon after being elected, US President Donald Trump promised a resurgence of coal, saying “we’re going to put our miners back to work”.32 The opposite occurred.

The New York Times reports that during the Trump presidency, 145 coal-burning units at 75 power plants were shut down, shrinking US coal-generated capacity by 15 per cent.33

A domestic boom in the extraction and burning of gas has been a key driver in America’s pivot away from coal, yet the environmental benefits of gas (often referred to as “natural gas” despite it being a fossil fuel) are questionable. Studies show that when accounting for “fugitive” methane emissions involved in its extraction and transportation, gas can be almost as environmentally damaging as coal.34

In the UK, much of the energy generating capacity lost with the shuttering of coal plants was replaced by an explosion in renewables, particularly offshore wind turbines. There, between 2014 and 2020, coal plant capacity plummeted 75%.27

In Australia, which is the world’s second biggest coal exporter,35 the picture is somewhat mixed.

Coal plants continue to be retired and plans to build new plants are being cancelled – yet there remains a stubborn push to build new coal power plants. However, while proposed new plants have been “announced” in recent years, experts say new coal plants no longer stack up financially and it’s highly unlikely they will be built.35

In a widely criticised move, the Australian Government in May announced it would spend up to AUD$600m building a new, 660MW gas plant at Kurri Kurri, in NSW’s Hunter Valley. Critics have questioned why taxpayers should fund projects the private sector won’t.

The gas plant would be used to provide “dispatchable”, on-demand energy at times of peak energy use, after the Liddell coal plant shuts down in 2023. Yet the Australian Energy Market Operator says there is no need to replace the Liddell plant and questions remain as to whether the new gas plant will proceed.36

Between 2018 and 2019, coal consumption fell in almost all industrialised nations, but grew strongly in many emerging economies.

For example, during the year coal consumption fell by 14.6% in the US, 23.2% in France, 17.4% in the UK, 20.7% in Germany and 3.3% in Australia.

In China, which accounted for 52% of coal consumption global, usage grew 2.3%. In Indonesia and Vietnam coal consumption surged by 20% and 30.2% respectively.

But emerging economies also saw the fastest rate of growth in renewables. In OECD countries – a group of wealth nations – energy from renewable sources such as wind and solar grew by 15.9% between 2018 and 2019, while in non-OECD countries renewable power generation surged by 45.9%.

More than 2,000 coal plants have been cancelled in recent years, yet hundreds remain on the drawing board, mainly in Asia. If all plans proceed it’s almost certain the world won’t reach its target of capping warming at 1.5°C.38

But it’s not all bad news. There is room for considerable optimism, particularly when it comes to renewables.

In its latest annual report, the authoritative International Energy Agency reported that for the first time solar energy had become not only cheaper than coal, but the “cheapest source of electricity in history”.39

Australia and South Asia director of energy finance at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, Tim Buckley, tells us this trend will only continue as technology continues to improve. Solar energy is “parasitic”, it destroys competition because it has “zero marginal cost”, Buckley says.

Everything hinges on how quickly the transformation occurs.

And experts say changes, from a political and legal perspective, can happen very quickly.

As evidence, Blair Palese, Global Climate Editor at Climate & Capital Media, points to three events in different parts of the world which all occurred on the same day in late May.

On 26 May 2021, an Australian court found that country’s government had a “duty of care” to protect young people from the climate crisis;40 a court in The Netherlands ordered Royal Dutch Shell to slash its carbon emissions by 45% by 2030;41 and, in the US, 61% of shareholders in fossil fuel giant Chevron defied management by voting in favour of the company cutting not just its own emissions, but those caused when Chevron’s customers burned its products.42

“A massive leap forward today,” Palese posted to social media.

Compare the Market commissioned Google Surveys to survey 503 Australian, 1,006 Canadian and 1,009 American adults throughout March 2022.

1 How College Kids Helped Divest $50 Billion From Fossil Fuels. Victor Luckerson, Time. 2014.

2 Tracking Academia’s Fossil Fuel Divestment. Zahra Hirji and Elizabeth Douglass, Inside Climate News. 2015.

3 Campaign Against Fossil Fuels Growing. Damian Carrington, The Guardian. 2013.

4 Leonardo DiCaprio Breaks Up with Big Coal. Aaron Smith, CNN Business. 2015.

5 DivestInvest. 2021.

6 Does the fossil fuel divestment movement impact new oil and gas fundraising? Cojoianu et al., Journal of Economic Geography. 2021.

7 Unburnable Carbon. Market Forces. Accessed 2021.

8 The Economic Geography of Fossil Fuel Divestment, Environmental Policies and Oil and Gas Financing. Cojoianu et al. 2019.

9 Does the fossil fuel divestment movement impact new oil and gas fundraising? Cojoianu et al., Journal of Economic Geography. 2021.

10 Divest Harvard. 2021.

11 Natalie Portman Joins Calls for Harvard to Sell Off Stocks in Big Energy Firms. Charlotte Alter, Time. 2015.

12 Mashable

13 Go Fossil Free. 2021.

14 Does the fossil fuel divestment movement impact new oil and gas fundraising? Cojoianu et al., Journal of Economic Geography. 2021

15 Desmond Tutu calls for anti-apartheid style boycott of fossil fuel industry. Damian Carrington, The Guardian. 2014

16 Does the fossil fuel divestment movement impact new oil and gas fundraising? Cojoianu et al., Journal of Economic Geography. 2021

17 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5C. IPCC. Accessed 2021.

18 Measuring the Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement. Arabella Advisors. 2016.

19 Ibid

20 Ibid

21 World’s biggest fund manager vows to divest from thermal coal. Joanna Partridge. The Guardian. 2020.

22 BlackRock holds $85bn in coal despite pledge to sell fossil fuel shares. The Guardian. 2021.

23 BlackRock votes against 49 companies for lack of climate crisis progress. The Guardian. 2020.

24 BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020.

25 BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020.

26 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5C. IPCC. Accessed 2021.

27 DivestInvest. 2021.

28 Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute. 2021.

29 China aims for ‘carbon neutrality’ by 2060. Matt McGrath, BBC. 2020

30 Global Energy Monitor. 2021.

31 China aims for ‘carbon neutrality’ by 2060. Matt McGrath, BBC. 2020

32 Trump made a promise to save coal in 2016. He couldn’t keep it. Ari Natter and Will Wade. Bloomberg. 2020.

33 ‘The Coal Industry Is Back,’ Trump Proclaimed. It Wasn’t. Eric Lipton, The New York Times. 2020.

34 Natural Gas is a much ‘dirtier’ energy source than we thought. Alejandra Borunda. National Geographic. 2020.

35 The World’s Biggest Coal Exporters. Katharina Buchholz, Statista. 2021.

36 Coalitions 600m gas fired recovery boost what you need to know. Adam Morton, The Guardian. 2021.

37 BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020.

38 Despite Pledges to Cut Emissions, China Goes on a Coal Spree. Michael Standaert, Yale Environment 360. 2021.

39 Solar is now the ‘cheapest electricity in history’. James Purtill, ABC. 2020.

40 Australian court finds government has duty to protect young people from climate crisis. Adam Morton, The Guardian. 2021.

41 Court orders Royal Dutch Shell to cut carbon emissions by 45% by 2030. Daniel Boffey. The Guardian. 2021.

42 Chevron investors back proposal for more emissions