The Burrow

As humanity continues to become more energy-conscious, our habits are starting to follow suit. As energy comparison experts, we’ve been eagerly tracking the emergence of both green and carbon neutral energy plans, given they give customers more choice when it comes to their electricity usage.

With the option to offset the carbon emissions produced from your energy usage or to be on a plan where the company generates renewable energy, there has never been a better time to compare your options and find a plan that best aligns with your personal preferences. Visit Compare the Market to find out more information.

And if you’re only just starting to understand renewable energy and the different ways it can be sourced, you’re in luck! We’ve put together a history of renewable energy sources so that you can understand the differences between them.

Our timeline tracks the evolution of the five oldest and most popular renewable energy sources – from their primitive use, through the industrial revolution and into the 21st century.

Plus, we’ll touch on the future of these energy sources – and the countries that are leading the way.

| A renewable energy source is generated from unlimited natural resources and is always being replenished, e.g. sun, water, wind. |

| HydropowerHydropower uses flowing water to power machinery and generate electricity. For example, grain grinding machinery on farms and hydroelectric energy plants to power cities. The fuel used in hydropower — water — isn’t diminished in the process. |

| Solar energySolar energy uses the sun’s rays for electrical generation and heating via solar cells in solar panels. This technology powers all types of things from wristwatches and households to satellites in space. Solar energy is an inexhaustible (until the sun burns out) and free source of energy. |

| Wind energyWind energy uses the same principles as hydropower, in that the source of energy (wind instead of flowing water) spins a wheel or turbine to generate electricity. While this is a renewable source of energy, it can’t make electricity on demand – as it relies on the wind to be blowing. |

| Geothermal energyThe word ‘geothermal’ comes from the Greek word geo (earth) and therme (heat). Geothermal energy harnesses the earth’s underground hot water and steam for heat and electricity generation. Geothermal energy is more readily available in areas affected by volcanism. |

| BioenergyBioenergy uses organic materials like wood as fuel. There are two types of bioenergy; biomass and biofuel. Biomass refers to organic matter like wood and animal/plant waste, while biofuel is extracted from organic matter to create fuels like biodiesel and ethanol. |

The four major roles of a renewable energy source

The benefits of using renewable energy instead of fossil fuels

Over the centuries, the water wheel evolved into a hydraulic turbine that generates electricity. Today, hydroelectric power stations are built in conjunction with dams to generate electricity for entire countries. Globally, hydropower is a major source of electricity and it’s still growing.

How does it work?

Hydroelectric power, also known as ‘white coal’, is the modern form of hydropower. Flowing or downward pouring water is captured and turned into electricity via turbines and generators, which is then fed into the electrical grid to be used in homes and businesses.

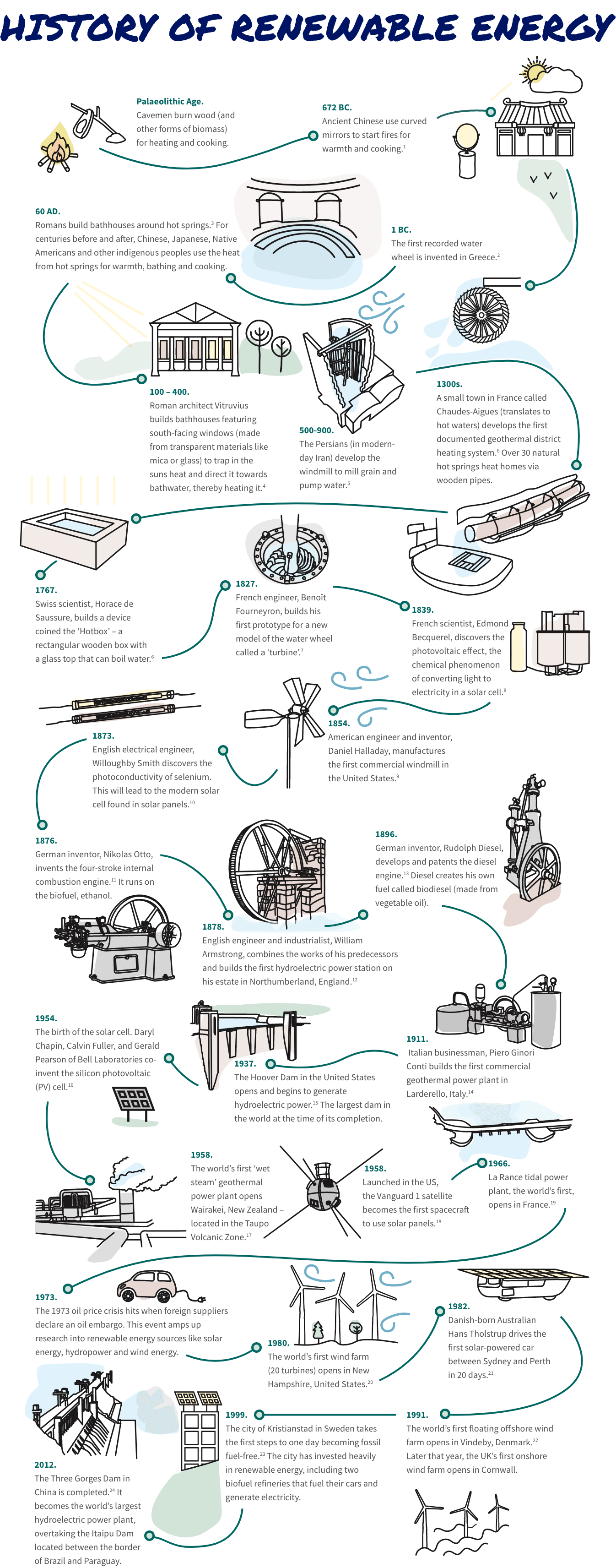

Timeline of hydropower

The first recorded water wheel is invented in Greece.1 People used flowing water to turn the wheel (of their mill) and ground wheat into flour. The waterwheel is a technological breakthrough, invented to reduce man and animal labour. China’s Han Dynasty also independently invented the water wheel around this time.2

By 500 AD, the water wheel is widespread throughout the civilised world.3 During this time it has a major impact on industrial development, as it enables man to produce goods without strenuous labour. By the 13th century, the water wheel helps medieval Europe become a military leader, as it’s used for manufacturing gunpowder and early steel.3

The water wheel is used extensively for milling, including sawmills, textile mills, paper mills, and flour mills. It also plays a key role in the industrial revolution throughout Europe and the United States, beginning in the 1760s.4 Many developing countries and rural farmers still use the water wheel today.

French engineer, Benoît Fourneyron, builds his first prototype for a new model of the water wheel called a ‘turbine’.5 Over the next decade, he refines his original design. By the mid-1850s, other countries adopt the Fourneyron-style turbine to power their industrial machinery.

English physicist, Michael Faraday, discovers electromagnetic induction and develops the first-ever transformer and electric generator.6 This technology will play a foundational role in the development of hydroelectric power.

British-American civil engineer, James Francis, improves upon the Fourneyron-style turbine, and invents the Francis Turbine.7 Francis applied scientific methods and testing methods to design a more efficient product.

American inventor, Lester Allan Pelton, invents the Pelton water wheel, an impulse water turbine that replaces bulky steam engines.8 In the next few years, the Pelton wheel will become the preferred turbine for hydroelectric power generation.

English engineer and industrialist, William Armstrong, combines the works of his predecessors and builds the first hydroelectric power station on his estate in Northumberland, England.9 The estate’s lake generates electricity through a turbine and powers an arc lamp.

The world’s first Hydroelectric power plant begins operations. Positioned along the Fox River in Appleton, Wisconsin, the Appleton plant produces electricity via the rushing water flow of the river.10

Germany produces the first three-phase hydroelectric system in Frankfurt.11 In the next decade, Polish-Russian, Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky’s three-phase power would prove superior to Thomas Edison’s DC and Nikola Tesla’s two-phase systems for transmitting power into a power grid.

Austrian Professor, Victor Kaplan, invents the Kaplan turbine, a propeller-type turbine with adjustable blades.12 An evolution of the Francis turbine, the Kaplan turbine provides greater efficiency in a range of water levels and flow.

The Hoover Dam in the United States opens and begins to generate hydroelectric power.13 The largest dam in the world at the time of its completion, the dam provides hydroelectric power for three US states – Nevada, Arizona and California.

La Rance tidal power plant, the world’s first, opens in France.14 Tidal power is a form of hydropower that converts the oceans tidal energy into electricity.

The Three Gorges Dam in China is completed. It becomes the world’s largest hydroelectric power plant, overtaking the Itaipu Dam located between the border of Brazil and Paraguay.15 The plant provides energy to millions (11 times more than the Hoover Dam in the states) using 34 gigantic generators.

The future of hydropower

According to Hydropower.org, hydropower should remain the world’s largest source of renewable electricity for many years to come due to its affordability, reliability and sustainability. They also predict significant growth from developing continents like Africa and Asia.16

The 2020 Hydropower Status Report revealed many other exciting developments in the sector, including:17

It took centuries for humans to harness and eventually transform the sun’s heat into electricity. The early uses of solar energy mostly pertained to heating and cooking. Today, the sun’s rays power many gadgets including cars, households, buildings and satellites in space.

How does it work?

A solar panel consists of numerous solar cells made from silicon. A solar cell captures the sun’s energy and converts it into electricity. This process is called the photovoltaic effect. Even on a cloudy day, a solar panel will generate some electricity.

Timeline of solar energy

The ancient Chinese use curved mirrors to start fires for warmth and cooking.1

Developed civilisations like the Chinese, Greeks and Romans build south-facing homes for supplementary heating.2

The emergence of solar water heating. When Roman architect Vitruvius returned from Greece, he notes their advanced solar architecture. This leads to Roman bathhouses featuring south-facing windows (made from transparent materials like mica or glass) to trap in the suns heat and direct it towards bathwater, thereby heating it.2

Swiss scientist, Horace de Saussure, builds a device coined the ‘Hotbox’ – a rectangular wooden box with a glass top that can boil water.2 The hotbox is used for cooking food and becomes a prototype for the world’s first solar collector – a device that heats water for homes and personal use.

French scientist, Edmond Becquerel, discovers the photovoltaic effect, the chemical phenomenon of converting light to electricity in a solar cell.3 This monumental discovery will eventually form the foundation of the solar panel.

French inventor August Mouchet and his assistant, Abel Pifre, construct the first solar-powered engine by converting solar energy into mechanical steam power.4 Although, Mouchet succeeded, the French government cut his funding and continued using coal-powered engines.

English electrical engineer, Willoughby Smith discovers the photoconductivity of selenium.5 Three years later in 1876, English physicist William Grylls Adams and his student, Richard Evans Day, discover that selenium produces electricity when exposed to light.6 This will lead to the modern solar cell found in solar panels.

American inventor, Clarence Kemp, patents the first commercial solar water heater, by improving upon Horace de Saussure’s hotbox over 100 years earlier.7

German theoretical physicist Albert Einstein publishes his paper on the photoelectric effect. This discovery lays the foundation of solar cells.8

The birth of the solar cell. Daryl Chapin, Calvin Fuller, and Gerald Pearson of Bell Laboratories co-invent the silicon photovoltaic (PV) cell.9 The solar cell is the world’s first device that converts light (sunlight or artificial) into electrical power by the photovoltaic effect. The invention allows man to harness enough solar energy to run electrical equipment.

Launched in the US, the Vanguard 1 satellite becomes the first spacecraft to use solar panels.10

Researchers from Exxon Corporation design a less costly solar cell, reducing the price from USD$100 a watt to $20 a watt.11 This rectifies the failed attempts in the 50s and 60s to commercialize the solar cell.

Once the solar cell becomes cheaper, a range of consumer goods become solar powered, including calculators, watches and outdoor lights. Plus, solar heating for homes and swimming pools becomes prevalent.

The U.S. Department of Energy launches the Solar Energy Research Institute, a federal facility dedicated to harnessing the sun’s energy.12

Danish-born Australian Hans Tholstrup drives the first solar-powered car between Sydney and Perth in 20 days.13

Eccentric billionaire, Elon Musk, founds Solar City. The aim of this company – and companies like it – is to make solar panels more efficient and less expensive while increasing their commercially availability.

The future of solar energy

Solar energy is set to become a bigger component of future electricity generation, with falling production costs and ease of access being the primary drivers of change.

In the International Energy Association’s (IEA) latest five-year forecast (2019-2024), renewable power capacity is set to expand by 50%, led by solar PV.14

Historically, many countries have subsidised the costs of solar energy to incentivise its citizens, including Italy, Australia and Germany. As technology advances, the cost of labour and materials may decrease, making solar energy a more affordable option for people to install.

Wind has powered sailboats and ships for over 5,500 years, however it wasn’t until much later that man harnessed the power of the wind for even greater utility. Today, many countries build wind farms (a group of wind turbines in the same area) to generate electricity – there are onshore, offshore, airborne and near-shore wind farms.

How does it work?

Wind energy captures wind through turbines and windmills, which can be used to power machinery or generate electricity. There are two basic types of wind turbines; the more common horizontal axis (like a propeller) and the vertical axis (shaped like an egg-beater). The vertical axis turbine can capture wind energy from all directions.

Timeline of wind energy

The Persians (modern-day Iranians) developed the windmill to mill grain and pump water.1 This new wind-powered technology soon becomes widespread across Europe and Asia.

The English develop tower mills, a tall brick or stone construction used in industry, e.g. sawmills.2 Also, during this period, the Dutch develop windpumps to drain water around the Rhine River Delta.3 Their design will inevitably become a national symbol.

American engineer and inventor, Daniel Halladay, manufactures the first commercial windmill in the United States.4 Halladay’s new design allows the windmill to automatically turn to face changing wind directions. Also, around this time, steel blades replace wooden constructions.

Scottish electrical engineer, Professor James Blyth, builds the world’s first electricity-generating windmill.5 Blyth’s design is said to have powered his Scottish home for 25 years. One year later, American engineer, Charles Brush’s company builds the brush wind turbine (a much bigger windmill) to generate electricity.6 In 1889, Brush sells his company to General Electric.

Danish scientist, Poul la Cour, writes a textbook on wind turbine design.7 Many of his design points hold up today, including the best wind turbines for electricity generation have fewer blades (three or two).

French engineer, George Darrieus, patents the Darrieus Wind Turbine (a vertical-axis wind turbine).8 The unique design is coined the ‘eggbeater windmill’ due to its aesthetic. While they produce less energy than horizontal bladed turbines, the Darrieus Wind Turbine still has an application today.

American brothers, Joe and Marcellus Jacobs, open a factory in Minneapolis. They sell small wind turbines, mostly to farmers to charge batteries and power lighting.9 This technology becomes commonplace across rural areas in the United States.

The world’s first megawatt-sized wind turbine is manufactured in Vermont, US.10 The tow-bladed design is connected to the local electrical system.

The 1973 oil price crisis hits when foreign suppliers declare an oil embargo. This event amps up research into renewable energy sources like wind energy.

The world’s first wind farm (20 turbines) opens in New Hampshire, United States.11

The world’s first floating offshore wind farm opens in Vindeby, Denmark.12 Later that year, the UK’s first onshore wind farm opens in Cornwall.12

Norwegian energy company, Equinor receives approval to build the world’s largest planned floating offshore wind farm in the Tampen area of the North Sea.13

The future of wind energy

In the future, many experts estimate wind energy will be one of the cheapest electricity generating sources, even rivalling fossil fuels.14 Why? Because it’s as cheap as coal, safe and easy to maintain.

According to the 2019 future of wind report, Asia will dominate the wind energy sector in 2050, followed by North America, Middle East and Africa, Europe, South America and Oceania.

The earth’s core contains magma and molten rock, and for thousands of years, humankind has used that heat via geysers and hot springs for heating, bathing and cooking. Today, many countries harness that hot water and steam to generate electricity. Geothermal energy is also used to directly heat buildings, dry crops and melt snow.

How does it work?

Geothermal systems extract steam or hot water from the earth’s core. A geothermal heat pump system captures underground reservoirs of steam and hot water to generate electricity. There are three types of geothermal power plants. Dry steam power plants focus on steam, while flash steam power plants use hot water. Wet steam or binary cycle power plants use a mixture of both.

Timeline of geothermal energy

Romans build bathhouses around hot springs.1 For centuries before and after, Chinese, Japanese, Native Americans and other indigenous peoples use the heat from hot springs for warmth, bathing and cooking.

A small town in France called Chaudes-Aigues (translates to hot waters) develops the first documented geothermal district heating system.1 Over 30 natural hot springs heat homes via wooden pipes.

The Hot Lake Hotel opens in Oregon, United States.2 The hotel/luxury resort is built alongside hot springs on the rural property. The Hot Lake Hotel is also the world’s first commercial building to use geothermal energy as its primary heat source.

The first geothermal district heating system in the United States is created in Boise, Idaho.3 The city capitalises on the region’s geology and completes two geothermal wells. Geothermal water heats over 200 homes and buildings.

Italian businessman, Piero Ginori Conti, develops the first geothermal-generated electricity.4 Conti powers five lightbulbs via a dynamo driven by a steam engine using geothermal energy. In 1911, Conti builds the first commercial geothermal power plant in Larderello, Italy.4

The first commercial geothermal heat pump is used to heat the commonwealth building in Portland.5 The geothermal heat pump is a central heating/cooling system that transfers heat to and from the ground. The use of this technology reduces the building’s energy costs.

The world’s first ‘wet steam’ geothermal power plant opens Wairakei, New Zealand – located in the Taupo Volcanic Zone.6

By the early 1980s, there are geothermal energy plants in multiple countries around the world, including Iceland, Indonesia, Turkey, the Philippines and Portugal. This is off the back of much government-funded research into the technology following the 1973 oil crisis.

Geothermal energy is behind other renewables sources for commercial use. Unlike solar, hydro and wind energies, geothermal energy is less readily available because it relies on geological characteristics (most geothermal resources are found along tectonic plate boundaries).

The future of geothermal energy

In 2015, the Global Geothermal Alliance said they aim to achieve fivefold growth in installed capacity of geothermal power generation and more than twofold growth in geothermal heating by 2030.7

Compared to fossil fuels, which are created over millions of years and are essentially non-renewable, bioenergy is created in a much shorter timeframe through photosynthesis (the process that enables plants to grow), making it a renewable source of energy. Bioenergy is the only renewable energy that converts into liquid fuels.

How does it work?

Bioenergy is a type of renewable energy that’s derived from biomass (plant-based materials). A highly versatile energy source, biomass can be burned to create heat or generate electricity. Biomass can also create bioproducts like paper and fuel transportation through biofuels; the two most common being ethanol and biodiesel.

Timeline of bioenergy

Cavemen burn wood and other forms of biomass for heating and cooking.

German-Russian chemist, Johann Tobias Lowitz, invents pure ethanol, a biofuel. Ethanol is a colourless liquid made from sugar or starch via fermentation.

People start to fuel their lamps with biofuels like vegetable oil and animal fats.

German inventor, Nikolas Otto, invents the four-stroke internal combustion engine. It runs on the biofuel, ethanol.1

German inventor, Rudolph Diesel, develops and patents the diesel engine.2 Because petroleum isn’t available, Diesel creates his own fuel called biodiesel (made from vegetable oil).

Henry Ford builds his first automobile, the Ford Quadricycle Runabout.3 It runs on an ethanol-powered motor. In 1908, Ford develops the Ford Model T – it runs on ethanol, gasoline or a combination of the two.4

Coal-powered electricity begins to displace wood as a fuel source for residential heating and cooking.

Prohibition prohibits alcohol in the United States. Unless mixed with gasoline, ethanol is no longer an acceptable fuel to power cars.

The post-war era decreases the need for biofuels like ethanol. Trucks and cars almost exclusively use fossils fuels like petroleum, as it’s considered cheaper and more efficient.

Gas and coal-powered electricity replaces wood as the primary source of energy for heating and cooking in households around the developed world.

The world’s first biodiesel commercial manufacturing plant opens in Austria.5 In the next decade, further plants will open across Europe and in the United States. The growth of biodiesel is driven by countries seeking to reduce their dependence on imported fossil fuels.

The city of Kristianstad in Sweden takes the first steps to one day becoming fossil fuel-free. The city has invested heavily in renewable energy, including two biofuel refineries that fuel their cars and generate electricity.6

Today, the use of biofuels has stagnated because gasoline and diesel are cheaper than biofuels to produce. What’s more, biofuels use crops that could be used for food, causing a production choice between food and fuel. However, some countries are turning the waste from plants like sugarcane into liquid fuels and chemicals.7

The future of bioenergy

The future of bioenergy is not as bright as other forms of renewable energy due to their high cost of production. This barrier to entry forces most investors and governments away from heavily investing in biofuels like ethanol and biodiesel.

Although, as previously mentioned, turning plant waste into biofuel (closed loop biofuel) is a viable fuel method, which many countries, including China are exploring.8

While renewable energy is the future, most households still use traditional means for gas and electricity. So, if you want to find a more competitive deal, it pays to compare energy plans.

Get a quote today using our free electricity and gas comparison tool.

Brought to you by Compare the Market: Making it easier for Australians to search for great deals on Energy Plans.