Endometriosis. For the 700,000 plus Australian women and girls diagnosed with this debilitating disease,1 it needs no introduction. For others, however, it’s still widely misunderstood.

What is endometriosis?

Endometriosis is a painful disorder that, according to Endometriosis Australia, ‘…is present when the tissue that is similar to the lining of the uterus (womb) occurs outside this layer and causes pain and/or infertility’.2

The Australian Coalition for Endometriosis (ACE) states the disease affects one in ten women in Australia and while it can widely cause severe pain and infertility, symptoms will be different for every woman and girl affected.3

ACE also said this disease costs Australia billions of dollars in healthcare, lost productivity and absenteeism. What’s more, girls with this condition can see their schooling, social growth and career path affected.

Dr Peta Wright, a gynaecologist who specialises in adolescent gynaecology at Eve Health, stated that a family history of endometriosis, such as a mother or sister with the disease, makes women and girls ‘seven times more likely to have endometriosis’.4

There’s no known cure for this condition, and medical opinion around its exact cause is still divided.

What are endometriosis symptoms?

Dr Wright explained that strong and persistent pain throughout a period and between cycles could be a sign of endometriosis. Other symptoms that occur around a period like migraines, nausea, spotting before the period and painful sex are also symptoms of this disease.5

Dr Wright explained that strong and persistent pain throughout a period and between cycles could be a sign of endometriosis. Other symptoms that occur around a period like migraines, nausea, spotting before the period and painful sex are also symptoms of this disease.5

Endometriosis Australia also pointed to fatigue, pain when urinating or passing bowel movements, heavy or irregular bleeding and frequently having to empty the bladder as other potential signs of the disorder.6

Dr Wright noted that ‘symptoms become apparent after a few years of getting periods, and girls are often told to suck it up. Although endometriosis can be diagnosed in young women, severe endometriosis usually presents in the twenties to forties.’

The elusive endometriosis diagnosis

It’s quite common for symptoms to be attributed to something else and become normalised, which is a big reason why diagnosis takes an average of seven to twelve years.

Jessica Taylor, President of the Endometriosis Association, added, ‘for the majority of women, it is often when they first get their period and they’re often told the pain is normal’.7

Taylor emphasised it’s crucial for women and girls to listen to their bodies.

I encourage them to seek a second, third, fourth, fifth, 20 opinions if they need to. If they truly feel something in their body isn’t quite right, then they need to listen to that. No matter how many times the doctor will tell them there’s nothing wrong or if it’s in their head, they need to push on and be their own advocate.8

The Federal Government published the National Action Plan for Endometriosis in 2018. The plan highlighted different steps the Australian Government plans to take to combat endometriosis and raise awareness.

The plan provides $2.5 million of funding for scientific research, running education programs in schools, and putting $1 million of funding into increasing awareness among medical professionals.9

‘Symptoms become apparent after a few years of getting periods, and girls are often told to suck it up.’

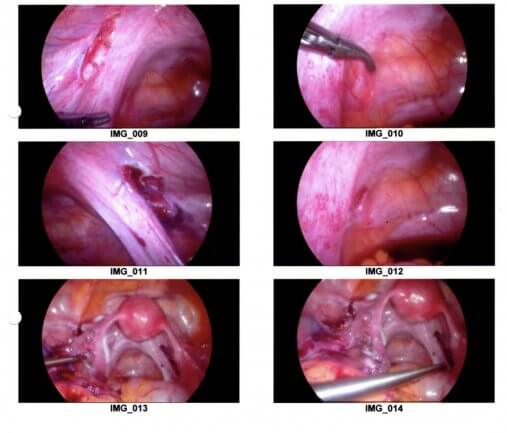

The National Health Plan for Endometriosis states that because the symptoms of endometriosis can vary between women and girls, invasive surgery is the only way to get a definitive diagnosis. Such a diagnosis is typically carried out by a laparoscopy.

| A laparoscopy, or key-hole surgery, involves making small incisions in the abdomen and feeding a light tube and camera through to examine inside the pelvis and abdomen.10 11 |

Images of endometriosis taken during a laparoscopy. Courtesy of Endometriosis Queensland

Images of endometriosis taken during a laparoscopy. Courtesy of Endometriosis Queensland

How is endometriosis classified?

In their paper Using Location, Color, Size and Depth to Characterize and Identify Endometriosis Lesions in a Cohort of 133 Women, Barbara Stegmann et al. notes the disease commonly appears as patches, spots or lesions that are red, white, brown or black – though it can also be somewhat clear or a mix of these colours. Endometriosis can also appear throughout the body, not just around the uterus.12

Once endometriosis is identified during surgery, it’s classified into one of four stages, ranging from mild (stage I) to severe (stage IV). The different stages are based on the number of endometrial patches, scarring, adhesions, their size and placement in the body. However, there are limits to how beneficial the classification system is for sufferers.

Taylor explains that it doesn’t matter what stage the disease is at, as women with stage I may be in as much pain as a woman with stage IV, despite few visual signs. Likewise, a woman with stage IV endometriosis may not experience any pain.13

What is the effect of endometriosis on pregnancy?

Women with endometriosis are not necessarily infertile, although it can make it more difficult for them to have children.

Roughly a third of women with endometriosis will experience trouble conceiving.14 Endometriosis can also leave women with a higher risk of complications during pregnancy and at birth.15

A common misconception about endometriosis is that having a baby will cure the condition. While symptoms may improve after a pregnancy, the National Health Plan said this might only be temporary due to changes in hormone levels, and the endometriosis symptoms can return.16

Jean Hailes for Women’s Health, a national not-for-profit women’s health organisation in Australia has a number of resources on endometriosis.

What treatment is available for endometriosis?

While there’s no current cure for the debilitating condition, endometriosis can be treated during a laparoscopy. Taylor explains that the surgeon will excise or burn off endometrial tissue, which can help reduce the severity of the disease.17

While there’s no current cure for the debilitating condition, endometriosis can be treated during a laparoscopy. Taylor explains that the surgeon will excise or burn off endometrial tissue, which can help reduce the severity of the disease.17

Dr Wright stated that surgery is just the beginning. While it can diagnose and remove endometriosis, it can’t fix other factors that may contribute to your overall pain, such as pain nerves that have become sensitised and pelvic floor muscles that have become too tight and tense over time.18

Furthermore, endometriosis can grow back, even after a successful surgery.19

Women with endometriosis might find that physiotherapy can help reduce the impact the disease has on their life.

Eve Health physiotherapist Alex Diggles noted that repeated pelvic pain could lead to muscles becoming tight, stiff and unable to work properly.

‘It can be hard for muscles to “un-learn”, and this is the role of physiotherapy,’ Diggles said.20

Dr Wright also said regular painkillers, like ibuprofen and paracetamol, typically aren’t effective and GPs may recommend hormone therapy. This therapy can involve the pill or an intrauterine device (IUD).21

Certain foods, such as gluten and dairy, can make the inflammation worse. Dr Wright notes a low FODMAP (standing for Fermentable Oligosaccharides; Disaccharides; Monosaccharides; and Polyols) diet could sometimes be beneficial.22

Covering the cost of endometriosis treatment

Dealing with endometriosis can become expensive. To receive a laparoscopy, your GP will need to refer you to a specialist, such as a gynaecologist. This appointment may incur out-of-pocket expenses, and you may then be put onto a public waiting list to have the laparoscopy surgery at a public hospital.

Dealing with endometriosis can become expensive. To receive a laparoscopy, your GP will need to refer you to a specialist, such as a gynaecologist. This appointment may incur out-of-pocket expenses, and you may then be put onto a public waiting list to have the laparoscopy surgery at a public hospital.

Medicare can cover the cost of the surgery in a public hospital, and provide a rebate should your GP refer you to other specialists, such as a physiotherapist or psychologist, as part of a treatment plan. Depending on the specialist fees, you might still be out-of-pocket for each of these appointments.

Women with endometriosis might like to pursue treatment for their condition through the private system. A combined private hospital and extras health insurance policy can cover various avenues of treatment.

Having private hospital cover allows you the option of seeking private treatment, which may give you the opportunity to choose your doctor and have a private room in the hospital (both subject to availability), and avoid public hospital waiting lists.

When using multiple health services for endometriosis treatment, an extras policy can help cover the cost of the treatment outside of hospital, including those visits to a physio, psychologist, dietician and more.

Private health insurance can also help pay for hormone therapy medications prescribed by your doctor, as some of these medications aren’t covered by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). The PBS is an Australian Government subsidy which caps the cost of some medications to make them more affordable. Private health won’t cover medications that are included on the PBS.

Don’t forget that even with private health insurance, you could still face out-of-pocket expenses when in hospital or seeking additional out-of-hospital care; this can include excess payments and ‘gap payments’. You may also be subject to waiting periods before you can claim payments towards treatment.

As such, it’s important to talk to your doctor and specialists to make sure you’re well aware of any out-of-pocket expenses whether you’re going through the public or private healthcare system.

If you’re looking for more information or someone to talk to about endometriosis, QENDO has a support line for those suffering from the disease.

Sources

[1] Development of the National Action Plan for Endometriosis. Department of Health, Australian Government. 2018.

[2] What is Endometriosis. Endometriosis Australia. 2019.

[3] Endo Facts. Australian Coalition for Endometriosis. 2019.

[4] Interview with Dr Peta Wright. Eve Health. 2019.

[5] Period Pain and Young Women. Peta Wright, Eve Health. 2018.

[6] What is Endometriosis. Endometriosis Australia. 2019.

[7] Interview with Jessica Taylor. Endometriosis Queensland, Australian Coalition for Endometriosis. 2019.

[8] Interview with Jessica Taylor. Endometriosis Queensland, Australian Coalition for Endometriosis. 2019.

[9] National Action Plan for Endometriosis. The Hon Greg Hunt MP, Minister for Health, Department of Health, Australian Government. 2018.

[10] National Action Plan for Endometriosis. The Hon Greg Hunt MP, Minister for Health, Department of Health, Australian Government. 2018.

[11] Laparoscopy. Healthdirect, Department of Health, Australian Government. 2017.

[12] Barbara Stegmann et al, 2008. “Using Location, Color, Size and Depth to Characterize and Identify Endometriosis Lesions in a Cohort of 133 Women” Fertility and Sterility. Volume 89, Issue 6, Pages 1632 to 1636.

[13] Interview with Jessica Taylor. Endometriosis Queensland, Australian Coalition for Endometriosis. 2019.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Interview with Dr Peta Wright. Eve Health. 2019..

[16] National Action Plan for Endometriosis. The Hon Greg Hunt MP, Minister for Health, Department of Health, Australian Government. 2018

[17] Interview with Jessica Taylor. Endometriosis Queensland, Australian Coalition for Endometriosis. 2019.

[18] Period Pain and Young Women. Peta Wright, Eve Health. 2018.

[19] Interview with Dr Peta Wright. Eve Health. 2019.

[20] Pelvic Pain and Physiotherapy. Alex Diggles, Eve Health. 2018.

[21] Period Pain and Young Women. Peta Wright, Eve Health. 2018.

[22] Interview with Dr Peta Wright. Eve Health. 2019.